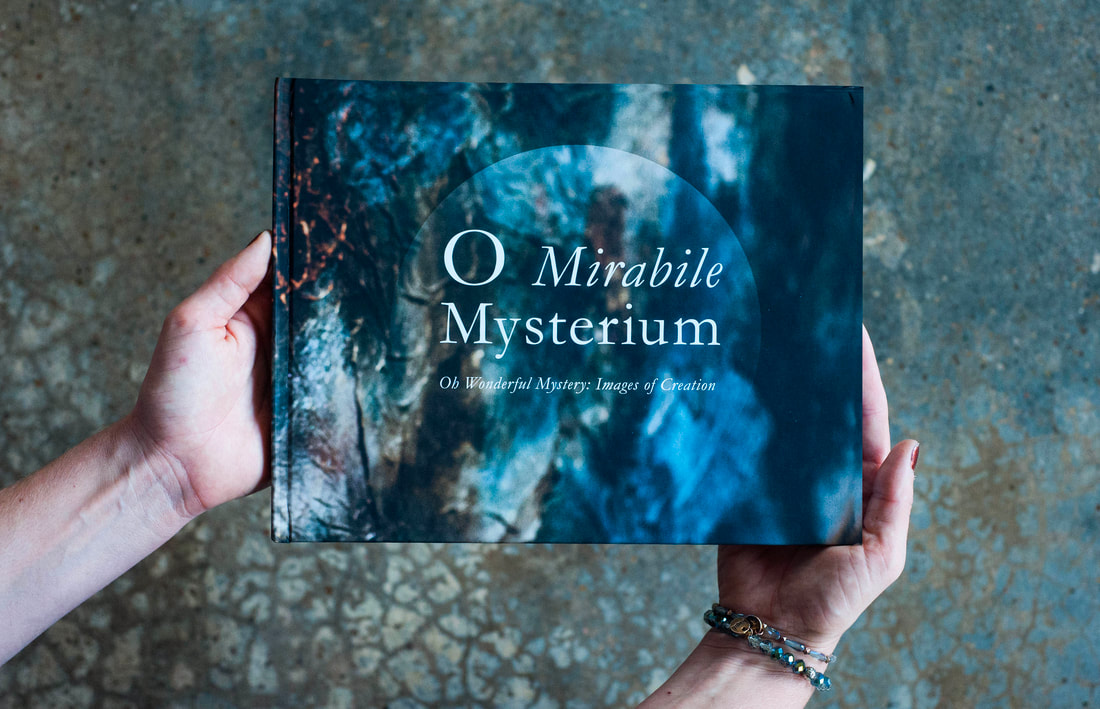

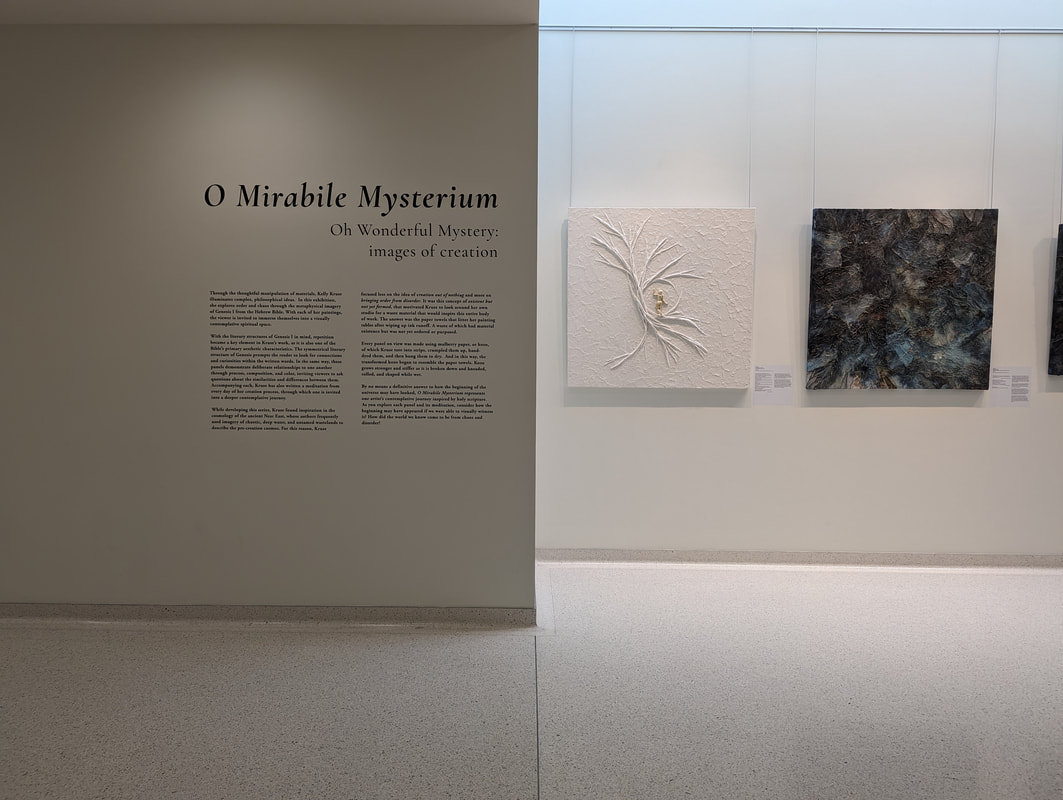

O Mirabile Mysterium

Oh Wonderful Mystery: Images of Creation

The process of making is its own reward: a meditation and a prayer, 2022

11 minutes, 30 seconds (headphones recommended)

Short film

I was a commercial photographer for five years prior to beginning my visual art practice, and photography has always been an integral part of my studio practice. But when it comes to video and film, I’m still a beginner. For several years, I have taken hours of footage, and some of it never sees the light of day. I'm a part of an artist collective called Creative Community, and I am often inspired by the way that my fellow artists are so brave in trying and sharing new projects and mediums, and so I wanted to push my visual practice into a new medium for this exhibit.

In this film, I’ve used the same materials, techniques, and processes that I am using to create my body of work on creation. All shots were either created by documenting my physical process of making the paintings or studies, or they were created by taking intimate closeups of my tools and materials.

11 minutes, 30 seconds (headphones recommended)

Short film

I was a commercial photographer for five years prior to beginning my visual art practice, and photography has always been an integral part of my studio practice. But when it comes to video and film, I’m still a beginner. For several years, I have taken hours of footage, and some of it never sees the light of day. I'm a part of an artist collective called Creative Community, and I am often inspired by the way that my fellow artists are so brave in trying and sharing new projects and mediums, and so I wanted to push my visual practice into a new medium for this exhibit.

In this film, I’ve used the same materials, techniques, and processes that I am using to create my body of work on creation. All shots were either created by documenting my physical process of making the paintings or studies, or they were created by taking intimate closeups of my tools and materials.

ABOUT THE WORK

I have had a desire to illuminate the Genesis creation accounts since late 2017, when I first heard a lecture on ancient Near Eastern cosmology by Dr. Tim Mackie from a conference on science and faith. Whenever I’m learning something new, I always have a desire to explore it fully in my studio, but sometimes it takes years to realize the idea.

My deepest hope for this project is to create a space for others to encounter the metaphysical imagery of creation in scripture, and for it to take center stage over the physical imagery. It is important to say that I have come to be convinced by my study of the text that any tensions between science and faith in creation are merely perceived–that is to say–when Creation is handled in the scriptures, it is not intended to be an account of the biological-material unfolding of the universe, and so to try to ask it to function as one demands answers from the text it wasn’t intended to provide. This doesn’t mean science is irrelevant–on the contrary, it is deeply relevant. But as Dr. William P. Brown says so poignantly in his book, The Seven Pillars of Creation, “Wisdom can turn the dividing wall between science and faith into a porous membrane through which selected ideas can flow.”

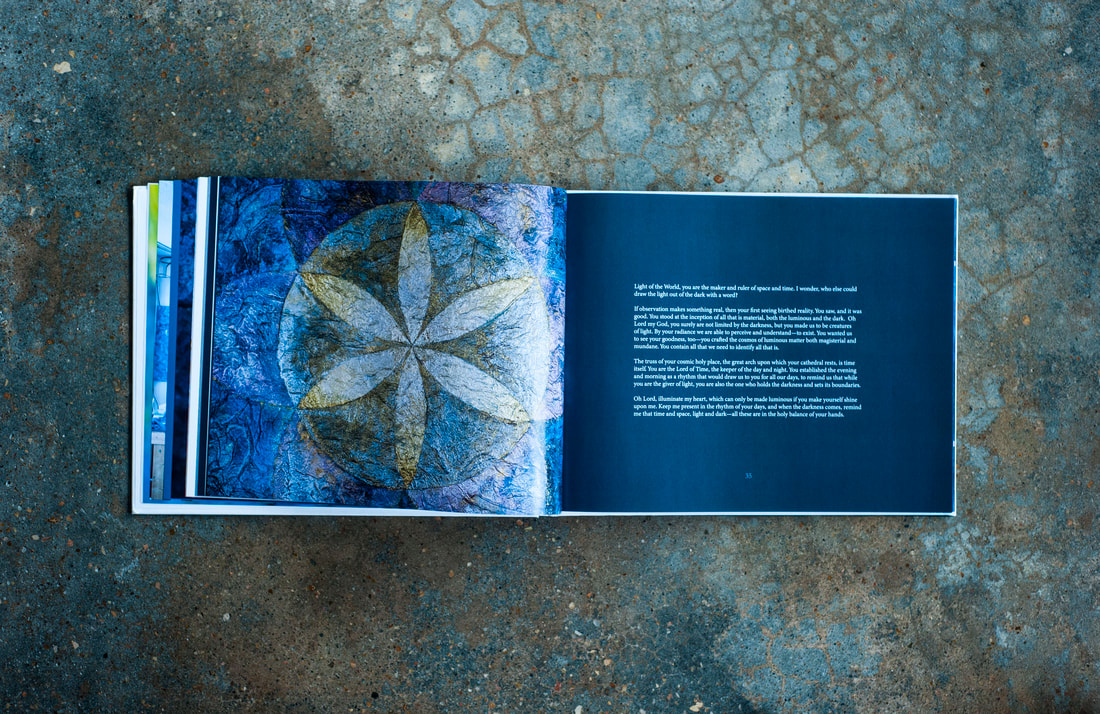

Inspired by the Hebrew phrase, תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ (Tohu va-Vohu), which Tim Mackie translates “wild and waste,” I looked to a waste material in my studio for inspiration for this entire body of work. I looked toward something that had material existence but had no purpose—paper towels I had used to collect ink runoff, that had grown crusty and sparkling. According to my studies, the author of Genesis would likely have categorized these materials as non-existent and formless. Inspired by these paper towels, I began hand-dying torn strips of kozo, or mulberry paper. The paper I’m using is made from 100% mulberry bark, and I buy it in large sheets. It has ten times the archival lifespan of cotton paper. It is made up of tiny fibers that knit together when the paper is worked with water, distressed, crumpled, folded, and unfolded. The more I work the paper, the tougher it gets. It can be worked by layering many sheets until it becomes stiff, and it can even be oiled to resemble leather.

Significant for my purposes, kozo is always shaped through water. Without water, the paper couldn’t be transformed and strengthened. When I sculpt and roll the paper, I do it wet. I bring strips of it from water and wring it out and let it dry, and then I cut, tear, collage, or sculpt the paper, ordering it into a physical artifact. The process is tedious, but that tedium comes from repetition. Repetition is one of the Hebrew Bible’s foremost aesthetic devices. This repetition provides a space for me to remember my own baptism, my own bringing forth from water, through water, to the water. I am only halfway through the project, and I am surprised by the freedom and ideas that have flowed from this one material: kozo. For me, it is proof that limits can create spaces of flourishing.

I have had a desire to illuminate the Genesis creation accounts since late 2017, when I first heard a lecture on ancient Near Eastern cosmology by Dr. Tim Mackie from a conference on science and faith. Whenever I’m learning something new, I always have a desire to explore it fully in my studio, but sometimes it takes years to realize the idea.

My deepest hope for this project is to create a space for others to encounter the metaphysical imagery of creation in scripture, and for it to take center stage over the physical imagery. It is important to say that I have come to be convinced by my study of the text that any tensions between science and faith in creation are merely perceived–that is to say–when Creation is handled in the scriptures, it is not intended to be an account of the biological-material unfolding of the universe, and so to try to ask it to function as one demands answers from the text it wasn’t intended to provide. This doesn’t mean science is irrelevant–on the contrary, it is deeply relevant. But as Dr. William P. Brown says so poignantly in his book, The Seven Pillars of Creation, “Wisdom can turn the dividing wall between science and faith into a porous membrane through which selected ideas can flow.”

Inspired by the Hebrew phrase, תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ (Tohu va-Vohu), which Tim Mackie translates “wild and waste,” I looked to a waste material in my studio for inspiration for this entire body of work. I looked toward something that had material existence but had no purpose—paper towels I had used to collect ink runoff, that had grown crusty and sparkling. According to my studies, the author of Genesis would likely have categorized these materials as non-existent and formless. Inspired by these paper towels, I began hand-dying torn strips of kozo, or mulberry paper. The paper I’m using is made from 100% mulberry bark, and I buy it in large sheets. It has ten times the archival lifespan of cotton paper. It is made up of tiny fibers that knit together when the paper is worked with water, distressed, crumpled, folded, and unfolded. The more I work the paper, the tougher it gets. It can be worked by layering many sheets until it becomes stiff, and it can even be oiled to resemble leather.

Significant for my purposes, kozo is always shaped through water. Without water, the paper couldn’t be transformed and strengthened. When I sculpt and roll the paper, I do it wet. I bring strips of it from water and wring it out and let it dry, and then I cut, tear, collage, or sculpt the paper, ordering it into a physical artifact. The process is tedious, but that tedium comes from repetition. Repetition is one of the Hebrew Bible’s foremost aesthetic devices. This repetition provides a space for me to remember my own baptism, my own bringing forth from water, through water, to the water. I am only halfway through the project, and I am surprised by the freedom and ideas that have flowed from this one material: kozo. For me, it is proof that limits can create spaces of flourishing.

The exhibition coffee table book

Click images above for more details!